Communication through Tribal Paintings: A Case of Warli

Preface

Communication means to share thoughts and feelings. Language is undoubtedly the most effective tool of communication but certainly not the only means of communication. If one sees the evolution of man one finds that before man stumbled on the word he created music and different forms and shapes, danced and painted through which he communicated with his fellow beings. These are now referred to as art forms. Thus, art has been there throughout the ages, helping mankind to communicate. This paper is a humble effort to show that not only words but paintings also have the power to communicate.

Communication & Art

Although communication takes place in all spheres of life yet the kind of communication happening in the sphere of art activity or the art world is quite different from the communication which takes places in the world of science and technology or in our daily discourses. In art the communication takes place through different mediums and has a different code altogether. In other words art creates its own language to communicate. In art, it is not only what is communicated but how it is communicated which is equally important.

Tribal Paintings

There are various art forms that can be associated to the tribals and painting is one such form. These tribal wall paintings are considered to be the oldest and strongest medium of communication and have played a vital role in the progress of man in many ways. The timelessness of this art form, the universal language they speak, and the unbroken continuity of their dynamic tradition reflect the lifelong struggle, genius and unparalleled vision of the people who draw these paintings. What do they communicate is the study of this paper.

Warli Paintings

This art form derives its name from a small and simple tribe called Warli residing in the hinterland of Maharashtra and parts of Gujarat. However, the strong hold is in Dahanu and Talaseri talukas of Thane district, about 120 kms north of Mumbai.

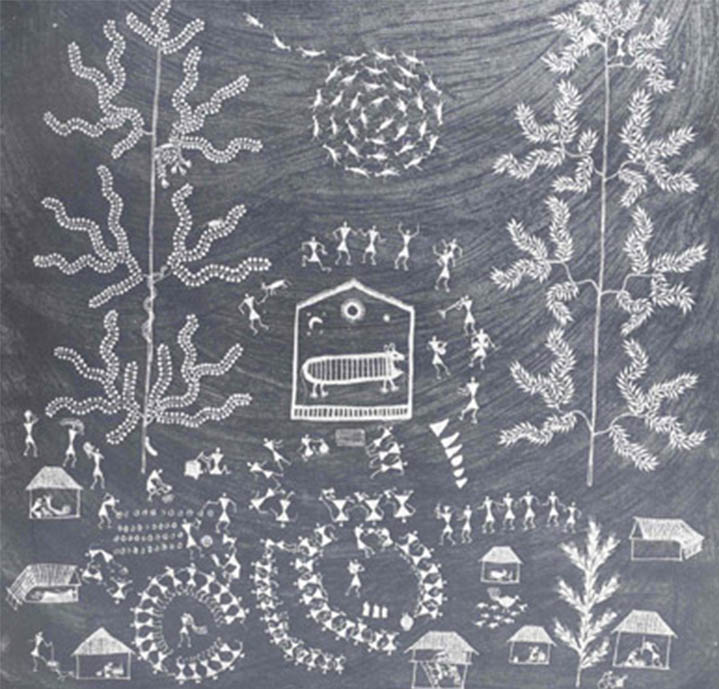

Among the various ceremonies, which the Warlis performs, marriage is the most important and auspicious event. Closely related to the Warli marriage is their art. Murals or the wall paintings drawn within a ritual context on the occasion of a Warli marriage are called Warli paintings. The act of painting these marriage murals is seen as lagna ‘chauk lihine’ (चौक लिहिणे) ‘writing’ the marriage chauk.

These paintings have come a long way from adorning the mud walls of their huts to a much prized art of today. With the entry of commerce various innovative themes along with new technique and materials have come into play. Along with the traditional marriage ‘chauk’ the recent paintings depict everyday activities, life scenes, myths and legends related to the Warlis. Now, one can find them on paper, fabrics, artifacts and a variety of other objects.

Dimensions of Warli Paintings

The aim of this paper is to bring out the uniqueness of this art and to understand its place as a unique medium of communication. It brings out this uniqueness through a study of the Warli paintings in terms of two most significant dimensions:

- The relationship between Warli art and nature

- The relationship between Warli art and life

All art forms take their inspiration from nature. So do the Warli paintings with nature as their immediate environment. Forest, wild animals, birds, plants and natural flora and fauna are the main source of their inspiration. They have a natural respect for all the vital natural elements. Their paintings not only portray religious beliefs but also convey the celebratory mood of the family and the whole community.

Relationship between the Warli art and nature:

As compared to so called civilized society their knowledge of nature preservation and environment (which is what makes them sustainable) and about the relationship between different life forms is far more sophisticated than what it is assumed it to be.

The relationship between nature and their art for the Warlis is that of reciprocity. To quote a distinguished scholar of tribal life and art, Dr. Govind Gare, ‘the basic principle of their life and their art is to give back to nature what they take from it”

“निसर्गाकडुन घेऊन निसर्गालाच देणे हेच त्यांचा जीवनेच आणी कले च सूत्र आहे.” (Dr Govind Gare; Warli Chitrakala: Marathi).

Warlis extract from nature only what is necessary and sufficient to live contently. For them nature is the primary source of their livelihood. Their respect for nature is clearly visible in their paintings. The flaura and fauna they depict are the plants and the trees amidst which they are born and live.

Vegetation

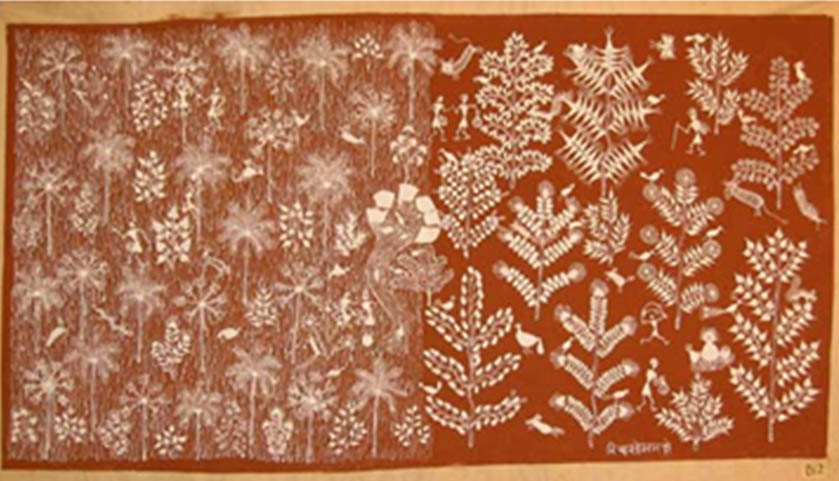

The presence of variously drawn tree forms in a Warli painting gives the feeling of aesthetic joy. The joy arises from the fact that they seem to sway and whirl along with rest of the painted forms. This gives the entire painted collage a breeze infusing look. What is even more important is that the feel in the painting is easily detectible.

The element of sensuousness please is also connected with element of felt breezing. The painted vegetation, therefore, invites a person’s will to own the painting. The element of ease and act of sale reach a good fit in the painted vegetation.

The swirling and interacting trees in the paintings make the cosmological statement also. They provide shade to the goddess Paalghat- the Mother Goddess of the Warlis. The trees are never cut, as they stand in eternal relationship with the Warlis. Like in real life, where their branches are used for lighting fires for warmth and as fuel for cooking, their life sustaining presence is preserved in the painting.

It is not incidental that the leaves of some the trees can be recogonised even in the drawings in the paintings. This happens due to the fact that the configurations of these trees and the leaves have gone into the unconscious of the Warlis, and when they paint, their unconscious starts speaking in the drawings (in the sense of Lacan).

Warlis do not worship all trees but certain trees like bel, papal, umbara and tulsi are regarded sacred and the dry woods of these trees are never used for fuel (Save 1945: 50). It is important to record that there is a whole range of the trees which make a mark on their paintings.

The most recognisable forms of the trees are date palm, the bashinga or kirmara tree, kiranjhad (sun tree) tamarind (chinch jhad), touch me not(lajra), fig (umbara), gooseberry (awala), mahua (mahua)and berry. In one basic sense the tree forms make the language of the Warli paintings. The presence of these forms is rooted in the reverence to nature amidst which the Warlis live.

These paintings thus celebrate the miracles of the flora which sustain the fauna of Warlis. The paintings include animals like fox, cat, cow, goat, horse, monkey, scorpion, tiger, peacock, hen etc. This natural richness of the Warli life works as the store house of forms from where they draw a huge inventory that dawn on their painting. This richness seems to be ultimate rationale for the commercial success that it has achieved so far.

Relationship between the Warli art and life

Warlis have remained, to this date, very much “in tune” with nature. Warli paintings display the innermost expressions of their relation with the nature and their life. In these paintings they paint their innermost beliefs, the life scenes in such a way that they look like representing the Warlihood.

Wagh-Baras: Tiger God Worshiped

Waghya or Waghoba is quite prominent among the life forms other than the Mother goddess that get high degree of centrality in Warli paintings. Waghoba is a conceptual lord of tigers in the nature. He is conceptual in the sense of being non-physical, an idea, who plays the protector. Given these features, the Warlis take him as the chief protector lord of cowherds.

As per the Warli belief Waghoba’s duty is to protect the cattle grazing in the forest. That is why he is given important space in their worship cycle. Wagh puja also known as Wagh baras is done in honour of the Tiger god. In their calendar it comes after Diwali, that is, after the first paddy is brought home.

Warlis believe if he is not propitiated, he can kill and eat them. The owners of the cattle propitiate him as the god of cattle. When their cattles are lost in the forests, they believe he brings them back.

Worship of the tiger god Waghoba has two aspects of it. One is concerned with the relationship of the Warlis with the animals whom they consider revered, and the second is related to their fear for the animal. Both of the aspects are justified. They revere it as that does not lead to the fear that a living tiger arouses. But this revering does not free them from the fear of the animal tiger. They cannot even afford to worship it, as an animal is not worshipped in their practice.

The paintings that paint Wagh Baras, therefore, are not just commercially capable, they very sensitively accurate within the cosmology of their beliefs. The distance that the Warli belief proposes between the physical being and cosmological power leads them not to paint Waghoba resembling to a living tiger. The distanced resemblance plays the needed role in its form that is drawn in painting.

Conclusion

In all their drawings the greatest aspect is the fluidity of line and lack of rigidity. Every element looks lively and animated. Expression through drawings and murals is their primary way of welcoming events and expressing individual and collective joy and happiness. Since their ways of expressing the personal and social moods are limited to drawing, dancing and musical forms they invest enormous aesthetic energy through their performances and in the art forms. Their paintings are their existence and they constantly enrich their world. One can therefore conclude that Warli paintings communicate their collective joy and happiness, their relation, dedication and reverence to nature, their deep seeded traditions- in short their total existence- to each other and to the rest of the world.

References

- Dalmia, Yashodhara 1988. The Painted World of the Warlis: Art and Ritual of the Warli Tribes of Maharashtra. New Delhi, Lalit Kala Akademi.

- Devy, G N.2006. A Nomad Called Thief: Reflections on Adivasi Silence. New Delhi, Longman.

- Gandhy, Khorshed M 1982. The Warlis: Tribal Paintings and Legends. Bombay, Chamould Publications and Arts.

- Heredia Rudolf C, Ajay Dandekar (Dec 9, 2000). Warli Social History. Economic and Political Weekly.

- Save, K J 1945. The Warlis. Bombay, Padma Publications.

- All India Handicrafts Board 1976. The Aesthetic Pulse of a People. New Delhi.