Modeling History in Hindi Lexicographical Practices

The Aim

The idea of modeling history in lexicographical practices stems from an abstract idea of lexicographical facts and their explanation, especially where lexicography is led by semantic centrality. The article begins with the creation of an abstract model of explanation. The model introduces the terms and conditions of history captured through centrality of meaning. The methodological insight used works with the choice of a ‘headword’ that is followed through the Hindi dictionaries placed in a chronological order. The insight helps to tap the progression or change, if any, in the meaning over the period of time in which dictionaries have been published. The database of this article is developed on the bases of the information gathered from monolingual Hindi dictionaries published since 1928. The article does two things:

- Creation of an abstract model of historical explanation in lexicography in general.

- Implementing the model and drawing conclusions relevant to the history of Hindi lexicography.

On Abstract Model

To develop the idea into a model of explanation should mean that lexicographical practice plays systematically over creation of meaning. Meaning change does not take place in dictionaries in a haphazard way. The model considers the practice over a period of time expressed as T. The time period (T) is realized as a span that runs between say t1 and tk.

The span is the time duration in which meaning progression occurs in lexicographical practice in a language. It happens in the way meanings are recorded in dictionaries in the period identified, and the way meaning changes come up in the recordings. In other words, it is suggested that history of lexicographical practice can be constructed out of the progression of change or otherwise of meaning. The architecture below captures the abstraction:

As captured through word relations:

The claim being put forward is that the observation of the recordings made in dictionaries over the time span running from t1 to tk are actual records of the history that the lexicographical practice makes, given the language.

Further, it is also claimed that the model thus created may act as a general model that captures the way history of lexicographical practice, including the practice in Hindi lexicography happens.

In other words the proposed model takes care of explanation of history in lexicography as a scientific practice in general, its realization with reference to lexicography of individual languages. Lexicography in different languages depends on the facts concerned.

Implementation of Abstract Model in Hindi Lexicography

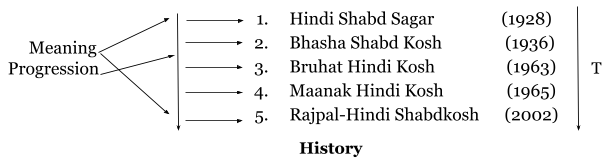

The abstract model of meaning progression, when implemented on the data collected from Hindi dictionaries proves a very efficient tool to record the development of Hindi lexicography. The architecture below has it:

The technique of selecting the meaning of a single headword from different monolingual Hindi dictionaries, published at different points of time in history, is used in this model. The dictionaries selected for the study are already mentioned in the architecture of the model. Only the first five meanings of the single headword are picked up from the above-published dictionaries. The first five meanings are selected because these are supposed to be the most common during the time of publication.

Mainly three approaches are adopted in this study to tap the historical progression of meaning in monolingual Hindi dictionaries. The first one is the change in preference of meaning, second one is dropping of meaning and the last one is the emergence of new meaning. These three approaches are evaluated in comparison with the reference point (t1) only to show the semantic changes happened to the Hindi lexicography. t1 for present study is Hindi Shabd Sagar published in 1928.

For the arrangement of the data a sequential order is maintained and one table is created. The complete information regarding the selected headword is given in appendices.

The Data

Regarding this article, in the frame of the above conceptualized model, Hindi word ‘गुरू’ is picked up from all above-mentioned monolingual Hindi dictionaries. All the dictionaries have tagged the word under two grammatical categories i.e. noun and adjective. Hindi Shabd Sagar has presented both the categories making two separate entries for the word ‘गुरू’, first for the adjective category and second for the noun. Other four dictionaries instead of giving two separate entries for the headword, have given only one entry tagged with two grammatical categories. Meaning is given separately for both the categories.

Etymology of the chosen headword is given properly in Maanak Hindi Kosh only. Other four dictionaries have given limited etymological information that the headword ‘गुरू’ belongs to the Sanskrit language.

Limitations for the Interpretation of the Data

- Only five published general purpose monolingual Hindi dictionaries have been selected for this survey.

- Only one headword is selected from those dictionaries.

- Only five meanings from the noun category are taken into account to make the study precise and easy to draw the conclusions.

- Unavailability of the first edition of these dictionaries is forced to assume the meaning of the current edition is like the first edition.

- It is already mentioned that this study follows the above-mentioned model in which Hindi Shabd Sagar (first published in 1928) is considered as t1.

- Hindi Shabd Sagar serves in this survey as reference point to compare the semantic changes that occur in dictionaries on the basis of ‘three approaches’ which are:

(a) Change in meaning preferences,

(b) Emergence of new meaning, and

(c) Dropping of meaning.

- Last but not least, is the observation of Collison regarding the study of lexicographic history is important to record. He writes (1982: 19-20):

Part of the fascination of studying the long histories of the dictionaries is that each dictionary relies to a certain extant on its predecessors, so that for each dictionary compiled today it is possible to construct a kind of genealogical tree in which its origins can (with sufficient patience) be traced back through several centuries. It is in fact impossible to compile a completely new dictionary. Even if no other dictionaries are physically consulted, the compilers’ efforts are inevitably drawn from their education and experience, both of which depend on a general consensus concerning derivation, history, pronunciation, meaning etc., of the individual words and phrases, all of which can be traced to the influence of the dictionaries published in the past.

In spite of all above-mentioned effects of early-published dictionaries, how and why the changes occur is the major point of discussion. All the arguments will proceed from the point of view of the above-mentioned monolingual Hindi dictionaries.

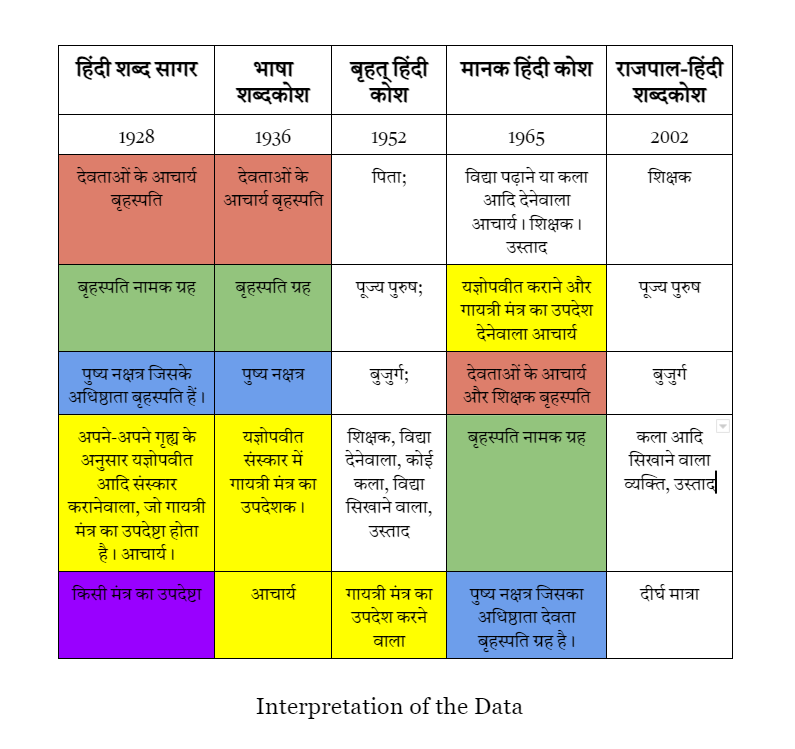

Meaning of headword ‘गुरू’ (noun) from 1928 to till date.

Change in Meaning Preferences

First meaning (देवताओं के आचार्य बृहस्पति) of the headword ‘Guru’ given in Hindi Shabd Sagar maintains its status in Bhasha Shabdkosh but it is dropped in Brihat Hindi Kosh. However this meaning comes at the third preference in Maanak Hindi Kosh but finally lost the relevance in Rajpal-Hindi Shabdkosh. The same thing happens to the second preference of meaning.

The third meaning (पुष्य नक्षत्र जिसके अधिष्ठाता बृहस्पति हैं।) has been preferred at the same position in Bhasha Shabd Kosh but snuffed out in Brihat Hindi Kosh. Again this meaning is revitalized and gets fifth preference in Maanak Hindi Kosh but finally disappears in Rajpal-Hindi Shabdkosh from the selected preferences.

Fourth preference of meaning of Hindi Shabd Sagar bifurcated (यज्ञोपवीत संस्कार में गायत्री मंत्र का उपदेशक and आचार्य) in Bhasha Shabd Kosh. First meaning of this bifurcation maintains its rank in Bhasha Shabd Kosh but the second part slips at the fifth level in the same dictionary. Again, the first part of the bifurcated meaning finds place at the fifth preference in Brihat Hindi Kosh but the second part slipped out. Maanak Hindi Kosh amalgamated the bifurcated meaning and enthroned it to the second preference. But the dictionary published after Maanak Hindi Kosh has not given importance to this meaning and finally it is snuffed out from the current dictionary.

The meaning which occurs at the fifth preference (किसी मंत्र का उपदेष्टा) does not find importance in any of the dictionaries published after Hindi Shabd Sagar. In other words this meaning is totally kicked out from selected preferences from the dictionaries published after Hindi Shabd Sagar. As per the above-tabulated information, it can be concluded that there is some similarity in between Brihat Hindi Kosh and Rajpal-Hindi Shabdkosh regarding the preferences assigned to the meanings. Both the dictionaries have at least three meanings that are common and preferred at the same rank.

But, in spite of having similarity for three preferences, the first preference of meaning of Brihat Hindi Kosh, does not find any place within the selected preferences in Rajpal-Hindi Shabdkosh. The fourth preference of meaning (शिक्षक, विद्या देनेवाला, कोई कला, विद्या सिखाने वाला, उस्ताद) of Brihat Hindi Kosh is bifurcated in Rajpal-Hindi Shabdkosh. The first part (शिक्षक) of this bifurcation got the first preference and the second part (कला आदि सिखाने वाला व्यक्ति, उस्ताद) got fourth preference in Rajpal-Hindi Shabdkosh.

Emergence of New Meanings

Five new meanings emerged within the specified preferences when Hindi Shabd Sagar is compared with later published monolingual Hindi dictionaries. But all these new meanings are recorded only in Brihat Hindi Kosh and in Rajpal-Hindi Shabdkosh. These new meanings are-

- पिता

- पूज्य पुरुष

- बुजुर्ग

- शिक्षक, विद्या देनेवाला, कोई कला, विद्या सिखाने वाला, उस्ताद

- दीर्घ मात्रा

Out of these five meanings, only one meaning (शिक्षक, विद्या देनेवाला, कोई कला, विद्या सिखानेवाला, उस्ताद) is continuing with slight change in preference in all dictionaries published after Bhasha Shabd Kosh. The same meaning is preferred at the fourth position in Brihat Hindi Kosh but uplifted to the first preference in Maanak Hindi Kosh. This meaning with bifurcation continues to be at the top of the preferences even in the latest Hindi monolingual lexicographic publication.

Dropped Meanings

The first meaning (देवताओं की आचार्य बृहस्पति), second (बृहस्पति नामक ग्रह) and the third (पुष्य नक्षत्र जिसके अधिष्ठाता बृहस्पति हैं) meanings are dropped in Brihat Hindi Kosh and the fourth (अपने-अपने गृह्य के अनुसार यज्ञोपवीत आदि संस्कार कराने वाला, जो गायत्री मंत्र का उपदेष्टा होता है। आचार्य।) meaning is dropped in the latest published dictionary that is Rajpal-Hindi Shabdkosh only. The fifth (किसी मंत्र का उपदेष्टा) meaning is snuffed out in all published monolingual Hindi dictionaries after Hindi Shabd Sagar within specified preferences.

Analysis

If changes happen to the meaning of words, we speak of semantic change. Textbooks of linguistics commonly list various types or categories of semantic changes. There is a considerable disagreement among scholars on the classification and terminology of semantic change. However the present study is not intended to classify the semantic changes in Hindi lexicography, rather it focuses on the meaning progression recorded in monolingual Hindi lexicography. Development of new words, priority given to meaning or transference in the meaning of old ones is actually a resonance of those changes that affect the thought of the person. When these changes are accepted and accommodated in the speech and writing of the society, the changes are documented in lexicographic products.

Sometimes changes take place in reverse order particularly in creation of terminological words. First a new terminological word created in a dictionary, then it goes through scrutiny and finally accepted in common speech and writing behavior of the society. There is a paramount work available on semantic change in Hindi language. This work of Hardev Bahri deals with changes that occur in the meaning of a considered lexical item or lexeme. To him getting at the rationale as to why the changes occur is the point of investigation. On the contrary this article reads history or calls it historical progression in the changes like the ones that Hardev Bahri may discover. To reiterate, it may be added that such changes in the present study are discovered with the help of the data gathered from the Hindi monolingual dictionaries published so far.

Interestingly, this can be observed from the table that all the five meanings of Hindi Shabd Sagar are not preferred within specified preferences at any place in the latest published dictionary that is Rajpal-Hindi Shabdkosh. It is clear that change is taking place in Hindi lexicography but “the Laws of meaning – change are not yet discovered and are probably undiscoverable” (Bahri 1985: 356). However, this article, at possible extent, will try to trace the reasons (not the laws of meaning change) behind these changes in published dictionaries.

Bahri (1985: 318) has broadly classified the reasons for semantic changes into two groups:

- Changes of meaning due to objective causes exterior to the mind.

- Changes of meaning due to subjective causes within the mind.

Both reasons are equally important for this article as well as to analyze the changes of meaning recorded in dictionaries.

Changes of meaning in Hindi monolingual dictionaries could be due to several (objective as well as subjective) reasons. Reasons of meaning change in lexicographical practices (as guessed in this dissertation from collected and tabulated data) are given below-

Change of hand – that is the person/s preparing the dictionary has/have changed and since a personal preference differs therefore order of meaning differs. This can be regarded as the subjective cause for semantic change within the mind of the editor. But changes in meaning due to personal causes have no chance of permanency except when they find agreement with the thoughts of the other people of the society. If the change of hand in dictionary compilation is a reason for a change in preference or meaning, it could be quite a bit of claim made that it is a change of meaning.

It is also important to observe that the habits of the lexicographers sometimes affect the meaning in the dictionary or on the preferences assigned to the meanings. Personal choices affect the meaning of the words. Here it would not be out of line to discuss an article, “Dictator, Gatekeeper, Tally Clerk or Harmless Drudge?” by Delbridge, Arthur and Peters, P.H. who discuss the role of the lexicographers in dictionary making. The roles (above-mentioned) are metaphors, and lexicographers choose their own. Discussing the role (Delbridge and Peters 1988: 33) they write:

Dictator, gatekeeper, tally clerk or harmless drudge: such are the role models that English lexicographers might follow. The dictator is perfectly authoritarian and prescriptive, noting errors only to warn against them. The gatekeeper is judicious-whatever gets through to the pages of the dictionary is there because it is deemed (at least for some contexts, or as a variant) to be or to have become all right. The tally clerk is mere teller, who would computer- count every word of every text, accepting the burden of not ignoring any usage, revealing variation through the record and change as it happens, for better or for worse, with no responsibility felt, no guidance given; entirely descriptive, not at all prescriptive.

It can not be denied that the change of hand is also a change of mind, that is two minds are engaged in meaning making, preparation of the entry and its order at two different points of time. It makes sense to argue that minds located in language consciousness and meaning sensibility behaved differently in different times. This suggests that change in order of the meaning entry is really a change in the meaning perception.

It is observed that the dictionary produced in 1928 (Hindi Shabd Sagar) and in 1936 (Bhasha Shabd Kosh), has very close resemblance in meaning as well as in preferences. It might be due to the facts that-

- Time gap is one of the major causes of meaning change. If there is more time gap there is more chances of meaning change. But there is a very short time gap (only 8 years) between publication of both dictionaries, so there are very less chances of meaning change in the language.

- Probably Hindi Shabd Sagar has given nearly all the possible meanings of the headword and the compiler of Bhasha Shabd Kosh has no option but to choose the meanings at the same preferences.

- Both the dictionaries were published in the pre-independence notion of mind so there is similarity in meaning and preferences.

- The Bhasha Shabdkosh might be heavily drawn upon Hindi Shabd Sagar, therefore its meaning.

After the publication of Bhasha Shabdkosh, in 1952 Brihat Hindi Kosh was published, which shows striking differences in the meanings and the preferences assigned to the meanings in Hindi Shabd Sagar. The possible reasons for change in meanings in this dictionary might be due to:

- The considerable gap of time from the publication of Hindi Shabd Sagar, so there is possibility of some semantic changes.

- The change of language orientation. After independence there was a change in language orientation. Earlier it was Sanskrit, the driving force in giving meaning in the Hindi dictionaries but as things grew, Hindi as a separate and independent language got importance in lexicographic products after independence.

- Change in hand / lexicographer/s therefore meanings and preferences are changed.

If it is true that at the time of publication of Brihat Hindi Kosh some meaning changes have taken place in Hindi dictionaries, then what are the possible reasons that the dictionary compiled in 1965 (Maanak Hindi Kosh) does not take these changes in consideration? Instead of giving meanings nearest to the dictionary published in 1952 i.e. Brihat Hindi Kosh, Maanak Hindi Kosh revives four meanings out of five selected preferences from Hindi Shabd Sagar.

The reason behind reconsideration of meanings and its preferences might be due to the similarity of hand in editing both dictionaries. The chief editor of Maanak Hindi Kosh is one of the sub editors of Hindi Shabd Sagar. To reiterate, compiler hand has considerable significance in the change of meaning in lexicography in general. Hence it can be true to the monolingual Hindi lexicography as well.

Importance of hand in the change of meaning or preference in dictionaries is the only one side of the truth. In addition to the change of hand there can be some other reasons responsible for the semantic changes in Hindi dictionaries. There is maximum similarity between Hindi Shabd Sagar (1928) and Maanak Hindi Kosh (1965) with reference to meaning and preferences. But the semantic changes, which have already taken place in Hindi lexicography, cannot be ignored so simply. This semantic change is the main driving force in giving top priority to the meaning, which even today has its relevance at first preference.

In 1928 (Hindi Shabd Sagar), the meaning शिक्षक, विद्या देनेवाला, कोई कला, विद्या सिखानेवाला, उस्ताद of the selected headword was not preferred within first five preferences but the same meaning got fourth preference in 1952 (Brihat Hindi Kosh). It is already mentioned that the same meaning is continuing at top preferences even in the latest published Hindi monolingual dictionaries. Now, it is reflected from the tabulated information that the language is developing and therefore some changes (in form of preferences) are taking place in specific contexts with time in history. The same is recorded in Hindi lexicography.

Being the same hand and the mind, what forces drive the compiler of Maanak Hindi Kosh to put the meaning at first preference which does not come even in the first five preferences in 1928 and in 1936? The question is simple but the answer cannot be obtained so easily. Probably, it is due to the recognition and importance of the semantic changes that have already taken place in the Hindi speech community. The compiler of Maanak Hindi Kosh could not discard the importance of the changes that have already taken place. Due to this reason only, the meaning which emerges at the fourth preference in Brihat Hindi Kosh, is upgraded to the first preference in Maanak Hindi Kosh and the same preference is continued till the latest published monolingual Hindi dictionary i.e. Rajpal Hindi Shabdkosh.

A comparative study of Hindi and Sanskrit vocabularies reveals that Sanskrit literature is nearly deprived of common, everyday and colloquial vocabulary. Sanskrit literature contains more religious, cosmological and philosophical terms and phrases compared to common, colloquial and popular terms and usages. On account of changed customs, environments and conditions these terms were either steadily forgotten or used with changed meaning.

The above argument could be another reason for meaning change in dictionaries, which is seen from the view point of change in value orientation in society. Earlier, Sanskrit was the driving force in providing meaning in Hindi dictionaries but as the things grow, Hindi as a separate and independent language starts taking rule, therefore new possibilities open up. Dictionary gets its own logical order of things. If there is a change in total perception, there is a progression from one sense of value to another sense and this progression has its historical consequence.

Bahri (1985: 326) observes that ‘with the growth of human institutions meaning changes take place’. With the increase of professions, trades and interests usage of the same words become restricted and differentiated. The progress in the general educational profession is attested by the changed meanings of Guru, ‘an elderly person, a preceptor, a teacher, a religious head’. Change in perception of meaning is reflected through the speech behavior of the people and the same is documented in the contemporary dictionaries.

After Independence, the government of India is working on standardization of Hindi that causes slight changes in grammar as well as in script too. Gradually, Hindi language finds acceptability in broader areas. This increase of acceptability causes considerable effect on meaning perception as well. Since the knowledge of Sanskrit is confined to very few people, the meanings related with Sanskrit literature are gradually disappearing from the lexicon of the common mass. This change, from meaning related with Sanskrit literature to the common spoken Hindi i.e. from pedantic language to the language of people is reflected through the changed preferences of meaning given in dictionaries compiled after Independence.

Seen from the descriptive and historical linguistics point of view it is quite logical to suggest that there is no meaning change as a matter of fact, this is just a change in formal properties of the language that are reflected through the lexicographic practice. Apparently it does not support or reject the article on meaning centrality and history of lexicography. To go back to the table, meaning entries in 1928 that is Hindi Shabd Sagar for the headword ‘गुरू’ are enlisted as below:

- देवताओं की आचार्य बृहस्पति।

- बृहस्पति नामक ग्रह।

- पुष्य नक्षत्र जिसके अधिष्ठाता बृहस्पति हैं।

- अपने-अपने गृह्य के अनुसार यज्ञोपवीत आदि संस्कार करानेवाला, जो गायत्री मंत्र का उपदेष्टा होता है। आचार्य।

- किसी मंत्र का उपदेष्टा

The first three meanings are the categories of physical cosmology. These terms are related to the Jyotish Shastra and Physics. Only the fourth and fifth meaning refers to social or occupational identity. The point of reference in these meaning entries is physical and interpretive sciences followed by professional and social identities. Bhasha Shabd Kosh (1936), which was published shortly after the publication of Hindi Shabd Sagar, invariably followed the trend of Hindi Shabd Sagar. The first three meanings are given denoting proper nouns and only the last two meanings are listed from the category of common noun. All the meanings enlisted from proper nouns category, are selected from Hindu mythology.

Brihat Hindi Kosh was published in 1952 after Independence. The entries of meanings for the headword Guru in this dictionary are as follows:

- पिता;

- पूज्य पुरुष;

- बुजुर्ग;

- शिक्षक, विद्या देनेवाला, कोई कला, विद्या सिखानेवाला, उस्ताद;

- गायत्री मंत्र का उपदेश करनेवाला;

Out of these five meanings no meaning is given either from the category of physical cosmology or from the category of proper noun. However, the first three meanings are actually the common relational terms used in society and the fourth and fifth meanings are referring to occupational identities. Point of reference for providing meaning in Hindi Shabd Sagar and in Bhasha Shabd Kosh is physical and interpretive sciences followed by professional and social identities. But Brihat Hindi Kosh snuffed out the preferences for physical and interpretive sciences. For this dictionary the reference point of giving meaning is only social and professional identities in selected preferences.

Now, the first five meanings for the headword ‘Guru’ in the dictionary published in 1965 that is Maanak Hindi Kosh are as follows:

- विद्या पढ़ाने या कला आदि की शिक्षा देनेवाला आचार्य। शिक्षक। उस्ताद।

- यज्ञोपवीत कराने और गायत्री मंत्र का उपदेश देनेवाला आचार्य।

- देवताओं के आचार्य और शिक्षक बृहस्पति।

- बृहस्पति नामक ग्रह।

- पुष्य नक्षत्र जिसका अधिष्ठाता देवता बृहस्पति ग्रह है।

The similarities and dissimilarities of Maanak Hindi Kosh with Hindi Shabd Sagar are already discussed, so there is no need to reiterate. The important point here for the discussion is the reference point. In spite of having maximum similarities, the reference point Maanak Hindi Kosh is in reverse with Hindi Shabd Sagar. The first two meanings in this dictionary are related with professional and social identities and the last three meanings are related with physical cosmology and Jyotish Shashtra. In other words the first two meanings refer to the common noun category and the last three the proper noun. Now the reference point has been reversed in this dictionary. The point of reference in these meaning entries for the headword ‘Guru’ is professional and social identities followed by physical and interpretive sciences.

At the last, the meaning entries given in 2002 that is Rajpal-Hindi Shabdkosh for the headword Guru is as follows:

- शिक्षक

- पूज्य पुरुष

- बुजुर्ग

- कला आदि सिखाने वाला व्यक्ति, उस्ताद

- दीर्घ मात्रा

This dictionary has mixed up the things. It bifurcate the meaning entry given for professional identity in शिक्षक and कला आदि सिखाने वाला व्यक्ति, उस्ताद. For the time being, if we take first and the fourth meanings as single identity, the reference point of this dictionary is from professional to relational or social identities. However, this dictionary has bifurcated the meaning between the teacher who teaches and the master who practices the art as well as teach. After bifurcation, this dictionary gives first preference to the meaning ‘teacher’ and fourth preference to the ‘master’ who is teacher as well as master.

It is observed by Bahri (1985: 326) that ‘At various periods of its semantic development emphasis shifts from one element to another. Sometimes the emphasis on one element may be so strong that the other elements are forgotten.’ This shift of emphasis is reflected through the preferences assigned to the meaning in dictionaries published at different points of time in history. He also observes that the shift of emphasis is the process of meaning transfer or restriction. The bifurcation made in the meaning from the professional category is not only a matter of chance but possibly it is done deliberately having some idea of meaning change that has already taken place in colloquial form of the language and the same thing is recorded in Hindi lexicography.

One bilingual dictionary and thesaurus that is The Penguin English-Hindi / Hindi-English Thesaurus and Dictionary was published in 2007. It was edited by Arvind Kumar and Kusum Kumar. This dictionary was published in three volumes. The first volume is English-Hindi / Hindi-English Thesaurus, second is an English-Hindi Dictionary with Index and the third volume is a Hindi-English Dictionary with Index.

It picks up the negative meaning of the headword Guru at fourth preference. This dictionary, certainly, is not the first bilingual dictionary that has picked up the negative meaning. This one is not the only dictionary which has picked up the negative meaning entry but some other bilingual dictionaries published earlier have provided negative meaning entry for this positive word. For example The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary by McGregor 1993:271 has given the meaning of this headword scoundrel with the tag pejorative.

The first five meaning entries for the headword Guru (Kumar & Kumar 2007: 357) which has been picked up from volume three that is Hindi-English Dictionary and Index are given below. The sequence of meaning entry is:

- अध्यापक (teacher) 335.6

- उपदेशक (preacher) 698.12

- कठिन (difficult) 511.11

- कुटिल (wicked) 749.7

- कूटनीतिकुशल (crafty person) 750.16

This dictionary has picked the first two meanings from the professional identities. It draws a demarcation line between the teacher and religious teacher (preacher). The third meaning belongs to the adjective category. But it is important to see the fourth and the fifth meanings. The meaning given at the fourth preference conveys total negative meaning whereas the meaning at the fifth preference can be used in an ironic sense.

In other words the negative meaning of the headword Guru has emerged in the senses of society at some point of time in history and the same is recorded in dictionaries. Possibly the seed of this negative meaning can be traced from the bifurcation made in Rajpal-Hindi Shabdkosh. But this is only an indication, not the clear-cut mention of the emergence of negative meaning of Guru in monolingual Hindi dictionaries.

However, it can be said that there is some progression of meaning in Hindi lexicography. The important thing is that the changes are recorded in bilingual dictionaries, not in monolingual dictionaries. There can be several possible reasons for not documenting this negative meaning in monolingual Hindi Dictionaries. Some of the guessed possible reasons are given below-

- Lack of New up-to-date Monolingual Hindi dictionary– Not even a single new up-to-date dictionary is published after the Rajpal-Hindi Shabdkosh. The Rajpal-Hindi Shabdkosh itself is its 17th edition published in 2002. The date of the first publication of this dictionary is not mentioned in the front matter of the dictionary. However it can be guessed that if this is its 17th edition, the first edition of this dictionary might have been published at least 15 years ago. If this is the case, it can be said that no new monolingual Hindi dictionary has been compiled during the past 25 years. So within this period, semantic change has taken place in the language which is not mentioned by the monolingual Hindi dictionaries.

- Lack of Evidence– perhaps this pejorative meaning has not been recorded in the writings of Hindi. Possibly at the time of compilation there was unavailability of proper citations and the negative meaning was not accommodated in dictionaries.

- Speech Behavior Overlooked – Possibly this negative meaning existed only in spoken form of the language and it might be ignored by the lexicographers.

- Dependency– Most dictionaries used the data from the earlier published dictionaries. Since no earlier published dictionary has entertained this negative meaning within given preferences, it is ignored by the editor/s of the new dictionaries as well.

- Personal Choices- This negative meaning is ignored deliberately for the defense of the dignity of the word Guru in the language.

- Prescriptivism– In order to prevent deterioration in language lexicographers might have felt that it is their duty to indicate, and if possible decide what the good usages are and what bad.

Observations

In the lieu of conclusion from the above analysis of meaning progression, the following observations seem to be important:

- The Abstract Model has been fully utilized with the Hindi data and it works.

- Meaning progression is clearly observed from the analysis of the collected data.

- Semantic development is the main guiding force in presentation of meaning entries in monolingual Hindi dictionaries.

- Semantic changes in Hindi language are reflected in published dictionaries with the help of changed preferences in meaning entries, emergence of new sense and dropping of meaning.

- Sometimes the personal preferences of a lexicographer plays a significant role in arrangement of meaning entries.

- It is observed that meanings of words related with Sanskrit literature are slowly disappearing from the monolingual Hindi dictionaries.

- Point of reference in Hindi monolingual dictionaries is shifting to the reverse from physical and interpretive sciences to the professional and social identities.

- The professional and social identities got the importance with the development of language and society after Independence.

- The pejorative meaning of many headwords have emerged but not picked up by the monolingual Hindi dictionaries. However, bilingual dictionaries have recorded pejorative meaning of the headwords.

As Nerlich (1990: 181) (As quoted in Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda 2004: 648) puts it, “Words do not convey meaning in themselves; they are invested with meaning according to the totality of the context. They only have meaning insofar as they are interpreted as meaningful, insofar as the hearer attributes meaning to them in context” (italics in original). If an interpretation of a word different from the intended interpretation is possible, and if this new interpretation is the one seized upon by the listener or learner and entered into the lexicon (“new” from the point of view of other speakers, that is), semantic change has happened.

References

- Bahri, Hardev (1985). Hindi Semantics. New Delhi, Manasdham.

- Bahri, Hardev (2002). Rajpal – Hindi Shabd Kosh. Delhi, Rajpal and Sons.

- Collison, Robert L. (1982). A History of Foreign-Language Dictionaries. London, Andre Deutsch.

- Das, Shyamsundar et al. Eds. (1928). Hindi Shabd Sagar. Varanasi. Nagari Pracharini Sabha.

- Delbridge, Arthur and Peters P.H. (1988). Dictator, Gatekeeper, Tally Clerk or Harmless Drudge? In

- Lexicographical and Linguistic Studies: Essays in Honour of G.W. Turner. Burton, T.L. & Burton,

- Jill (Eds.) (1988). Cambridge, D.S. Brewer.

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (2004). An Approach to Semantic Change. In The Handbook of Historical Linguistics.

- Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Eds. (2004).USA, Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Kumar, Arvind and Kumar, Kusum (2007). Hindi-English Dictionary with Index. In The Penguin English –

- Hindi / Hindi – English Thesaurus and Dictionary. India, Penguin Books India in association with

- Yatra Books.

- McGregor, R.S. Ed. (1993). The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary. New Delhi, Oxford University Press.

- Prasad, Kalika et al Eds. (1952). Brihat Hindi Kosh. Varanasi, Gyanmandal Limited.

- Shukla, Ramashankar (1962). Bhasha Shabd Kosh. Allahabad, Ram Narayan Lal Beni Prasad.

- Verma, Ramchandra et al. Eds. (1965). Maanak Hindi Kosh. Prayag, Hindi Sahitya Sammelan.